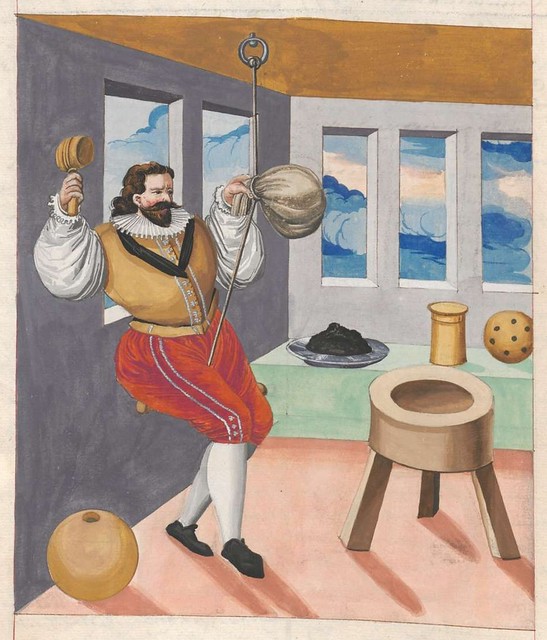

"They in the fort shoting agayn and casting out divers fyers,

terrible to those that have not bene in like experiences

...and in dede straunge to them

that understood it not; for the wildfyre

falling into the ryver Aven, wold for a tyme lye still,

and then agayn rise and flye abrode,

casting furth many flashes and flambes,

whereat the Quene’s Majesty took great pleasure."

['The Progresses and Public Processions of Queen Elizabeth..' 1823 by J Nichols] {pic}

"That the electric "spark of life" figured prominently in debates over the nature of life in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is well known. Less well known is the fact that prior to this period, gunpowder was often identified with the substances that were necessary to life, if not as a vitalistic spirit, then as an essential element in the animation of the body. The idea of a spark of life went back to ancient times, likening living beings to the glowing embers of a fire. In the Old Testament, for example, the wise woman of Tekoah begs for the life of her son, pleading "they will stamp out my last live ember." But from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, this vital flame was often equated with gunpowder. There was fire in the blood: not electric, but pyrotechnic fire."

['Sparks of Life' by Simon Werrett* IN: Cabinet Magazine Issue 32 Winter 2008/09]

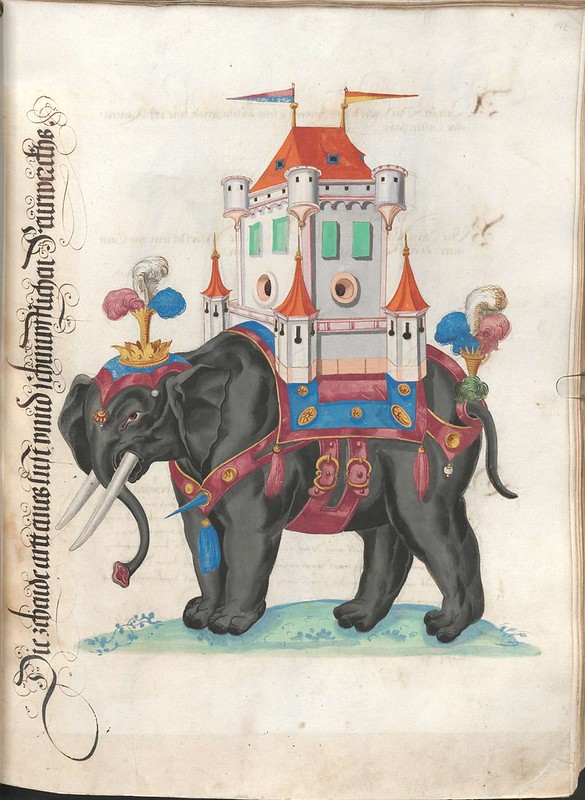

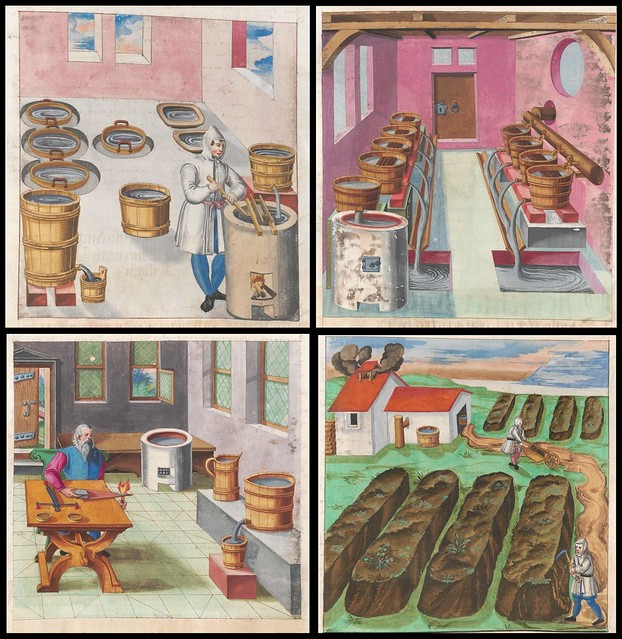

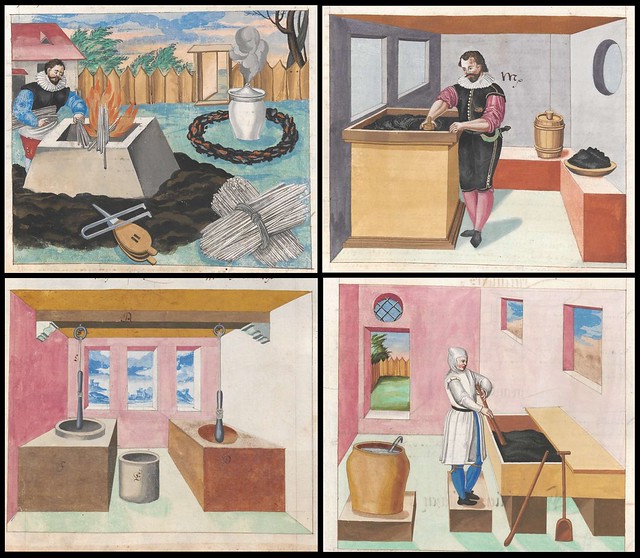

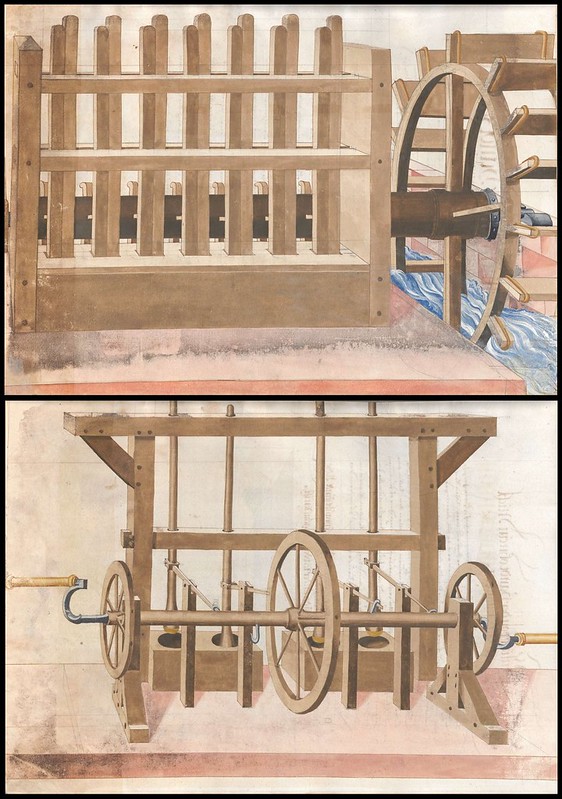

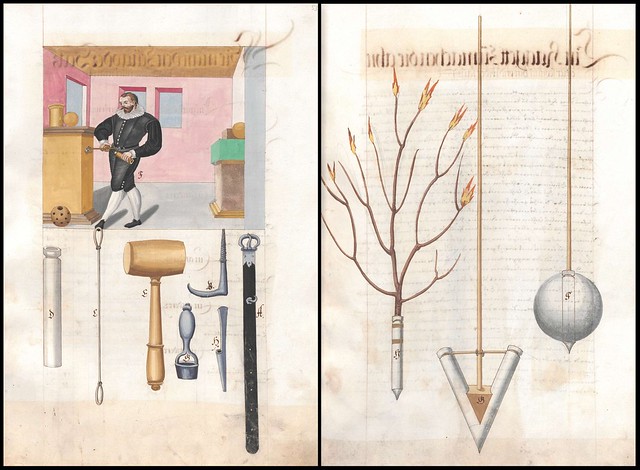

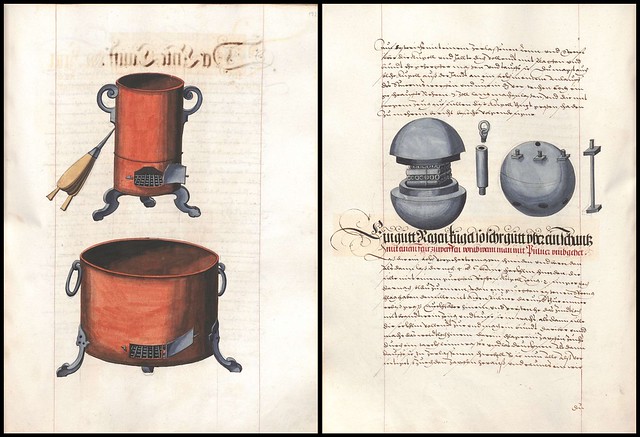

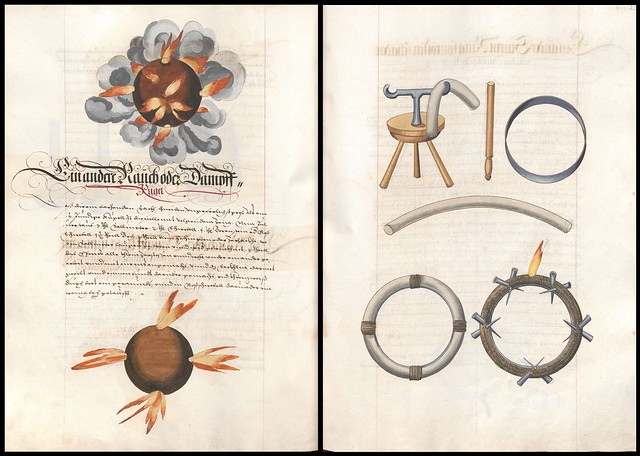

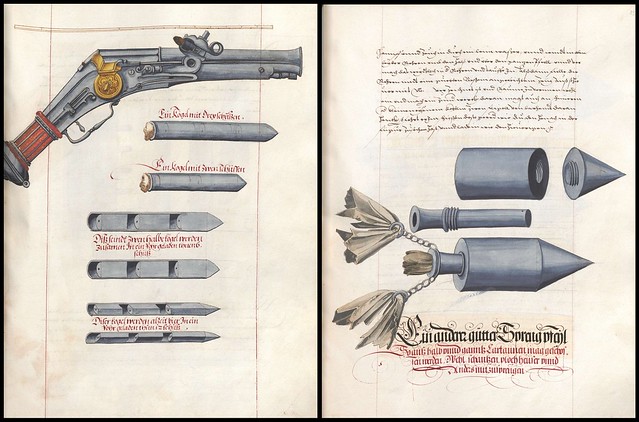

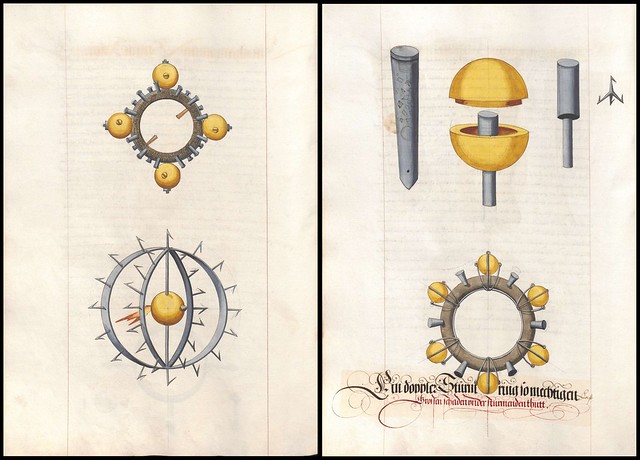

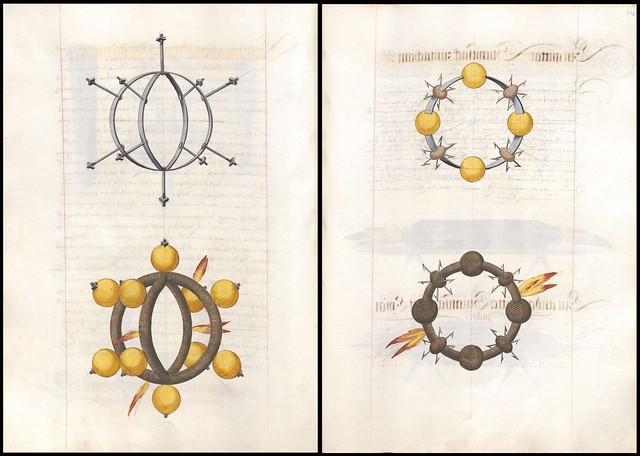

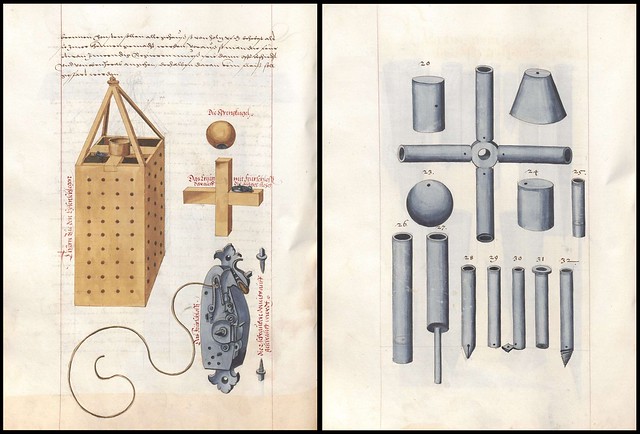

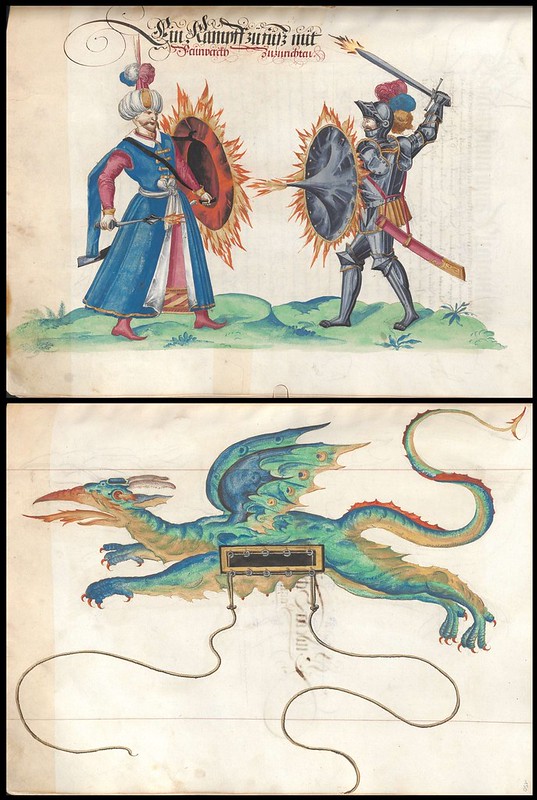

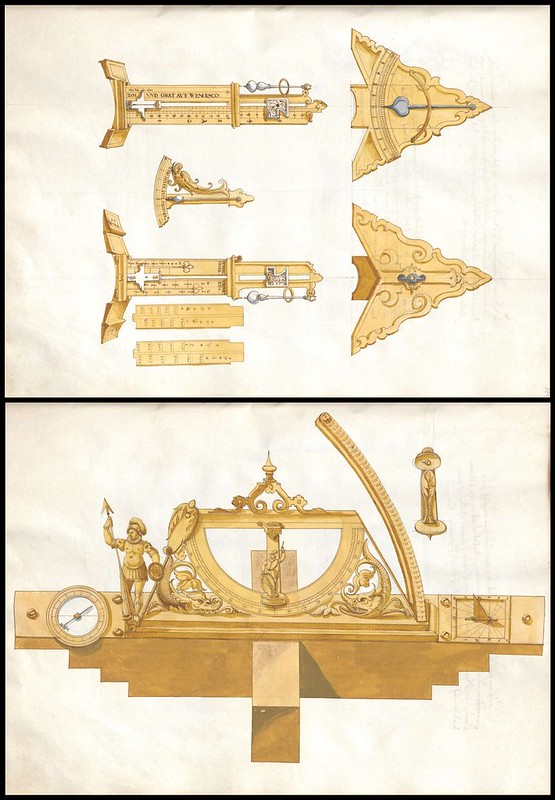

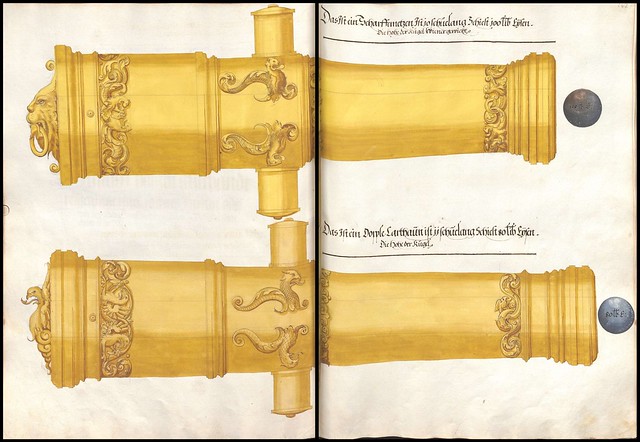

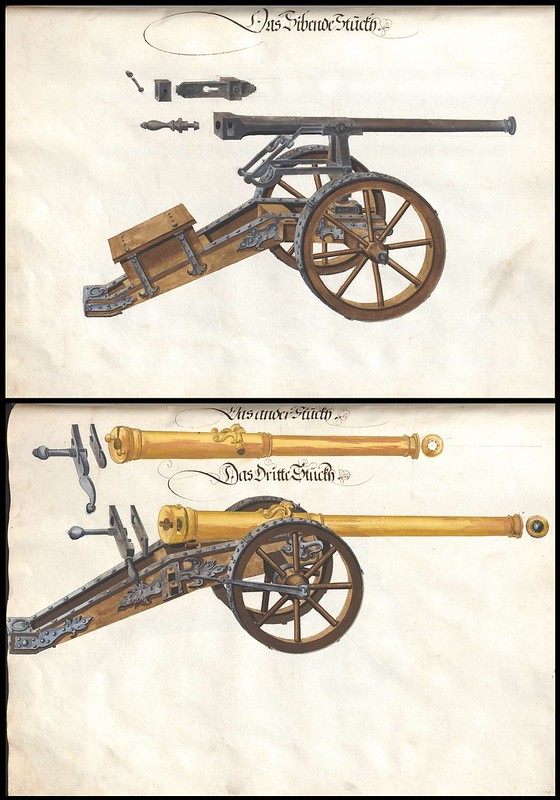

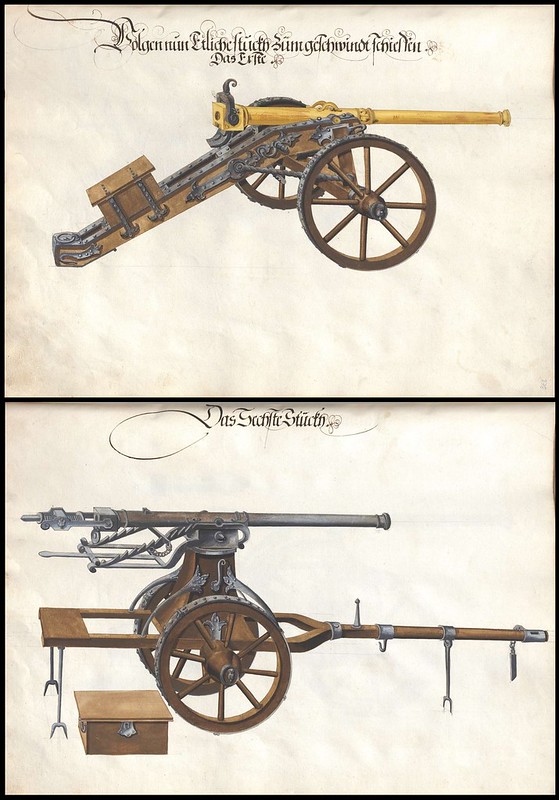

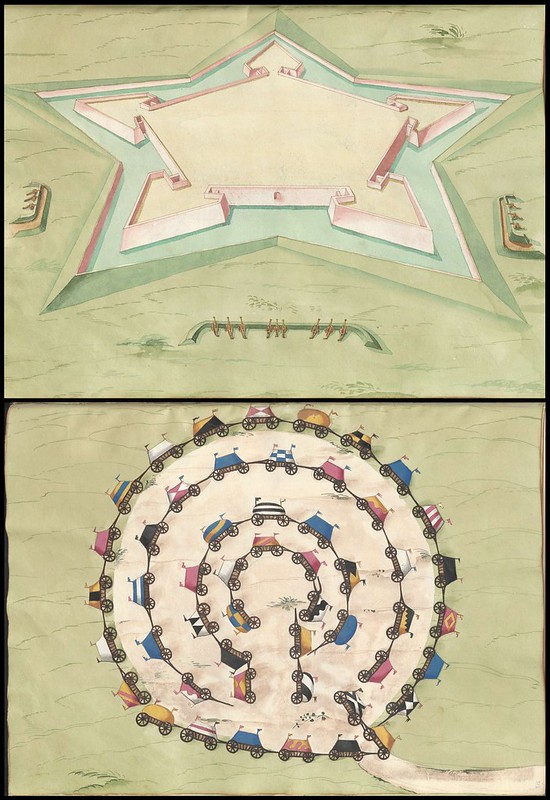

The images below come from an enormous hand-painted and hand-written gunsmithing and fireworks manuscript by Friedrich Meyer from 1594. 'Büchsenmeister und Feuerwerksbuch' is owned and hosted by BSB. It is one of the most comprehensive Early Modern tomes that I've seen on the broad subject of fireworks, encompassing as it does, in text and picture, the many facets of production and deployment of gunpowder and the pyrotechnical arts. The lack of web citations to this manuscript is presumably due to it's being a secondary compilation based on earlier works. There are two single full-page views below; the rest are mostly 2 or 4 pages spliced into single images, together with a couple of cropped miniatures. Background spots and staining have been mildly reduced.

"The origins of fireworks lay in China, but European fireworks followed a distinctive development after their introduction from the east in the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries. Early European fireworks were used for war, with rockets, bombs, fire tubes, and grenades being hurled against enemies through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

There were also peaceful fireworks, adding drama to church plays and festivals with squibs attached to flying angels or pyrotechnics made to represent the fiery mouth of Hell.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the fireworks of the battlefield and the church slowly merged into peaceful displays of military pyrotechnics, first in religious plays for the courts, and then in secular triumphs and performances based on classical allegories. By the close of the sixteenth century, many European courts employed gunner artificers to stage grand fireworks marking royal occasions, military victories, and the new year."

[by Simon Werrett (& others), from Werrett's essay, 'Watching the Fireworks' IN: Science in Context 24(2), 167–182 (2011), Cambridge University Press]

"Fireworks of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries [.] amounted to a form of artificial nature, showing suns, stars, comets, fiery exhalations, snow, rain, thunder and lightning. These effects were considered extremely powerful and deeply impressed the princely patrons and courtiers who used them as tools of political distinction. This distinction hinged on knowledge or experience of pyrotechnics. The gentleman or courtier was expected to be virtuous, partly by the habit of reading, and numerous new books on fireworks were published in the sixteenth century to offer instruction in the creation of pyrotechnic effects. Those who understood or had familiarity with fireworks then experienced them as pleasing diversions, while those who did not were imagined to be terrified as if by natural portents."

[Simon Werrett's essay, 'Watching the Fireworks' IN: Science in Context 24(2), 167–182 (2011), Cambridge University Press]

I've always enjoyed the whole genre of gunpowder and pyrotechnics books and manuscripts from the Renaissance and Early Modern eras - see combat posts for previous related - despite my general ignorance for how the concepts of fireworks spectacle and artifice operated in the world hundreds of years ago. The illustrations are always colourful and attractive and make for good posting fodder on basic terms, of course. I mean, I had some inkling that fireworks way back then were fairly different, but I wasn't particularly aware of the breadth or meaning of their application nor (especially) how they were regarded by people.

Many reference commentaries on the early fireworks publications have tended towards narrow approaches: the chemistry, the manufacturers, various histories, the people involved etc. So the lack of references surrounding Meyer's manuscript featured above quickly (fortuitously) pointed me towards a few recent publications by historian Dr Simon Werrett. I don't pretend I've just become enlightened or even much smarter, but Werrett (and at least one other that he references, and no doubt a few others) considers the subject matter through a wider lens, involving social history, philosophy, physiology, alchemy, magic, religion and metaphorical systems (among other considerations no doubt), giving this esoteric material a more comprehensive and nuanced explanation. Hence, the Werrett-derived quotes dominating above.

- 'Büchsenmeister und Feuerwerksbuch' by Friedrich Meyer (or Mayer) 1594 is available on the website of the Bavarian State Library. It is nearly 600 pages long, with very few blank pages as I recall.

- 'Sparks of Life' 2009 by Simon Werrett in Cabinet Magazine online.

- 'Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History' 2010 by Simon Werrett.

- Dr Simon Werrett teaches the history and philosophy of science at University College London. Some of his essays are linked there although membership of hosting institutions is most likely(?) needed to obtain full papers. Thanks to KH for her help in that regard!

- 'Incendiary Art: the Representation of Fireworks in Early Modern Europe' by Kevin Salatino 1998.

- Previously on BibliOdyssey: combat.

- Elsewhere: @BibliOdyssey -- BibliOdyssey -- BibliOdyssey -- biblipeacay.

- ADDIT: I just found out that the rss feed has been broken for a month. And here was me thinking that everyone had fallen out of love with me considering the declining visitation stats of late. Anyway, it's all fixed, although it worries more than a little that Google owns feedburner, the carrier/publisher of this site's feed. Please let me know if things go awry on the rss front after July 1, 2013 when GoogleReader is terminated.

No comments:

Post a Comment