Astronomy illustrated in the 1840s

"The want of a series of Plates for the illustration of the Science of Astronomy, of accurate, yet popular character, calculated for effective display, and still within a moderate compass, has led to the production of the present Work. The design comprehends 104 coloured Scenes, representing the Astronomical Phenomena of the Universe. These have been carefully executed from original drawings, paintings, and observatory studies; aided, occasionally, by appropriate pictorial embellishment, but with strict adherence to fidelity of detail. [..]

The illustrations form the miniature scenery of a public exhibition, such as is occasionally witnessed in lecture-rooms; the text presenting the substance, the order, and the actual delivery of what becomes, in the present instance, a FAMILY ASTRONOMICAL LECTURE. The prominent features of the present Work are, the novelty and simplicity of the plan, and the elegance of its execution. With its aid a family need not henceforth quit their own parlour, or drawing-room fireside, to enjoy the sublime 'beauty of the heavens;' but, within their domestic circle, may, without any previous acquirements in Astronomy, become their own instructors in a knowledge of its great and leading truths and phenomena.

The Lecture may be read aloud by a parent, teacher or any other member of a party, the Scenes being exhibited, at the same time, in the numercial succession corresponding to their order of description. It would be impossible to devise a more rational, or, to a well-regulated mind, a more cheerful mode of passing an evening; or of inculcating the Divine lesson, of looking 'through Nature up to Nature's God.'"

[Charles F Blunt, Introduction to 'The Beauty of the Heavens']

The Earth: its Form and Position in Space

"INDEPENDENTLY of the great interest we must take in such inquiries as lead to an accurate knowledge of the body on which we live, it is highly important to a clear understanding of its true nature, and the operations of the planetary system, that we make ourselves perfectly acquainted with the circumstances and the position of our earth, which is itself a member of that system; and, for us, holds the important place of the station, or observatory, whence we view and estimate the phenomena and evolutions of the whole. [..]

A little reflection, and a reference to common and well-known appearances observed in travelling, either by sea or land, readily convince us that the earth is of a spherical or globular form. Let a person take any station in a level country, or at sea, and carefully observe the objects within the range of his view; let him then advance in any direction, and, as he moves forward, the objects behind him gradually disappear, and new objects in his front come into view. [..]

The scene exhibits these effects, where the figures of the ships are shewn to become respectively more and more curtailed in their apparent height above the surface of the sea, as their distance from the spectator increases. Of the distant ship he sees only the upper parts of the masts; of the next nearer to him he sees the lower parts of the masts and rigging; but of the ship at the nearest point of distance, he sees, no only the masts entirely, but the hull of the vessel itself, down the surface of the water on which it floats, together with that portion of the surface which lies between the object and himself; of the ship more remotely placed, he sees nothing. These are appearances which can only be reconciled by assuming a spherical figure for the earth."

{I think this simple model shows:} the effects of centripetal and centrifugal forces, together with the pendulum and gravitational effects, on the orbital paths traced by planetary bodies and moons in the universe

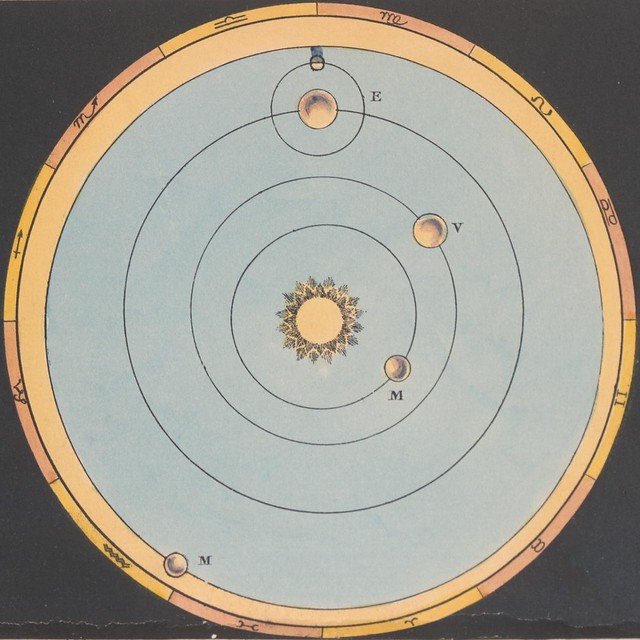

The Planetary System: Mercury, Venus, the Earth and Mars

The Earth, Inferior Planets, and the Asteroids Vesta, Juno, Ceres, and Pallas

[Some descriptive pages before these paragraphs:] "In the view we have just taken of the system, we have looked at the entire arrangement, independent of any restriction as regards the point from which that might be supposed to be taken. We imagined ourselves, for the moment, stationed at a distance that might be sufficient to afford a view of the whole, as of a a scene spread out before us. This simplification gave us a clear idea to the extent and general dimensions of the subject; but now that we are to inquire into the circumstances of each separate body in detail, we must consider our view as taken from the earth, the station from which our observations are naturally made.

It is, in some degree, necessary to have these two different points of view in our recollection: the one, because we know the sun to be the true centre of the system; the other, in which we are compelled to view the appearances of the heavens and planetary motions, as if the earth were really in the centre, because it seems so to us. The one, therefore respects the real situations and motions; the other respects their imaginary or apparent situations. The real view is sometimes called HELIOCENTRIC, a term compounded of the two Greek words, signifying, the sun in the centre: the apparent view is termed GEOCENTRIC, signifying, the earth in the centre."

The Moon at the Full

Mouseover the image for a feature map of the lunar disc!

Nomenclature of the Lunar Spots:

| A | B | C |

| Tycho** | Schickardus | Pitartus |

| D | E | G |

| Bullialdus | Gassendus | Grimaldus |

| H | I | K |

| Hevelius | Aristarchus | Kepler |

| L | M | N |

| Copernicus | Appennine Mountains | Archimedes |

| P | Q | R |

| Possidonius | Cleomedes | Arzachel |

| T | W | Y | Z |

| Sea of Nectar | Fracastorius | Lake of Death | Plato |

"Next to the sun itself, the moon is, to us, the most conspicuous of the heavenly bodies; and the changes she undergoes in her appearance are more remarkable and more obvious than those of any other objects in the planetary system, and her apparent motions are more rapid. Hence, the motions and changes of the moon engaged the attention of astronomers before much was known to them of those of the sun; and hence it was that the earlier inhabitants of the earth reckoned their time by the apparent motion of the moon, calculating by a lunar, not a solar year. [..]

The scene represents the face of the moon, as she appears through a powerful telescope, at the full, or, what is termed, in opposition. The surface of the moon, when viewed in this manner, presents a great diversity of irregular forms, and great differences of illumination; but the principal masses of light and shade are visible to the naked eye. Some spots resemble, in a striking manner, the appearance of mountains and valleys, and the effect of volcanic disturbances; and some observers have even imagined that they could distinguish volcanoes in a state of active combustion. [..]

The moon is not surrounded, like the earth, by vapours or clouds; for, whenever she is visible to us, she appears with the same serene, clear, and calm aspect. It is generally received opinion, that there is no water upon the moon; and hence we are entitled to infer, that none of those atmospherical phenomena which arise from the existence of water on our own planet will take place on the moon."

The Moon's Phases

"ALTHOUGH the varying phases of the moon are among the most frequently observed phenomena of the heavens, they are yet the most surprising and beautiful; owing to the frequency and the strict regularity of these changes of appearance and situation in the moon, the causes of the phenomena are little thought of by an ordinary observer. If the changes from new moon to full moon, and from full to new, happened only at long intervals, they would, without doubt, be considered the most extraordinary of all celestial phenomena."

Constellations of the Northern Hemisphere

"It may be readily imagined, that the splendour of the scene of the starry heavens, in appearance perpetually revolving around the earth, must very early have commanded the earnest attention of mankind; and that, long before any systematic cultivation of science, men must have remarked the regular changes of situation, in regard to the earth, of the stars apparently fixed in the heavens, and that, though they appear unequally and irregularly dispersed over it, they must, in some measure, have classed them, and reduced them to something like order, and that the most brilliant would chiefly attract their attention; and hence, that such arrangement of the whole would be made as to enable the learned to hold intercourse on the subject, without immediate reference to the objects themselves.

In what age of the world the artificial arrangement of the stars into constellations took place, is not known with precision, but it is most certain that it was antecedent to any distinct historical record."

Cassiopeia

"CASSIOPEIA lies directly opposite to Ursa Major: the fee of Cassiopeia are directed towards the head of that constellation, the interval between them being divided into nearly equal portions by the pole star. The figure is that of a woman seated on a chair, slightly clothed, with both hands raised, holding in the left, a branch of palm, and in the right, a portion of her head-dress."

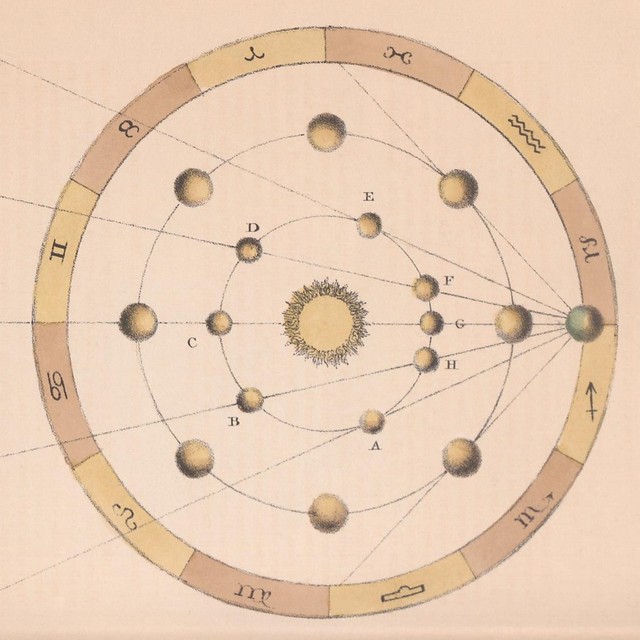

The Sun's Place in the Ecliptic

"THIS scene illustrates the meaning of the expression of the sun's place in the ecliptic. It has already been explained, that by the ecliptic is meant the imaginary circle in the heavens, in which the sun appears to move as seen from the earth, or the circle in which the earth appears to move as seen from the sun.

The zodiac is that portion of the heavens through which the middle of the ecliptic appears to run, and is portioned out into twelve parts, or divisions, each of which is termed a constellation; as Aries, Taurus, Gemini, &c. The sun, as seen from the earth, always appears in the ecliptic, and, consequently, in some of these constellations. That portion of the zodiac in which the sun appears, is termed its place in the ecliptic, the ecliptic being itself within the limits of the zodiac.

The scene shews the sun in the centre, and the earth in several points of its orbit round it; and beyond it is a circle, representing the constellations of the zodiac in their order."

The Apparent Retrograde Motion of the Planets

"THIS scene illustrates the apparent retrograde [backwards] movements of the planets Mercury and Venus. The outer circle of the scene is the circle of the zodiac, or stars, among which the apparent paths of those planets seem to be. In the centre is the sun; the circle of small globes, next beyond the sun, represents Mercury in his orbit; on the border of the scene, to the right, is a green globe, representing the earth.

Now, if we imagine the balls, representing Mercury, to move round in their orbit, beginning at the point opposite to the earth, and to move from right towards the left, the lines which are drawn from the earth through the planet at each stage of its progress, and extended as far as the zodiac, will shew to what parts of that circle the observer on earth refers the planet; or, which is the same thing, in what parts of it the planet appears to be from time to time."

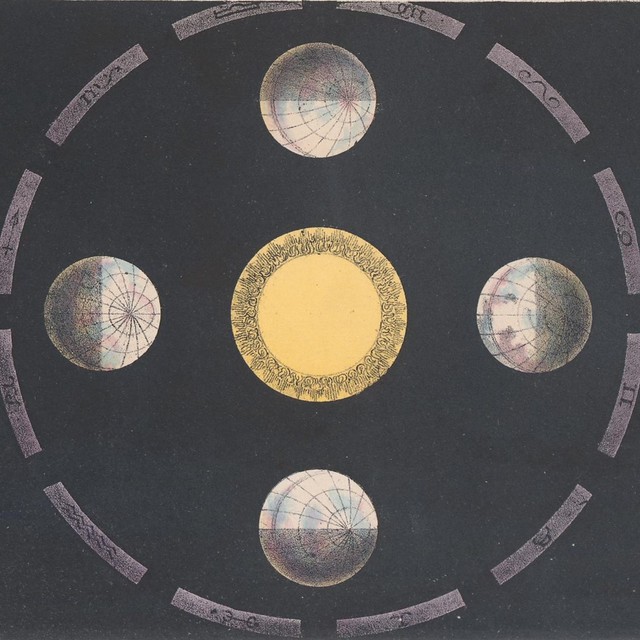

The Phenomena of the Seasons

"In this scene the sun is represented in the centre, surrounded by the earth, which is shewn in four principal points of view, according with its position during the seasons we term spring, summer, autumn, and winter. In each position the poles of the earth are in the same direction as in nature; and the boundaries of day and night, as regards the poles, are seen in each. On the outer side of the figures of earth, are the signs of the zodiac, by which we can understand what, in a former scene, was termed the sun's place in the ecliptic (or zodiac), at the four great points of the earth's orbit; and, of course through all the intermediate points."

The Moon's Surface - Kepler

"The accurate observations of the moon's surface was one of the earliest applications of the telescope. Its remarkable mountains and cavities, ridges and detached rocks, and annular spots, have been examined and drawn by different observers. [..]

The spot, Kepler, the subject of the scene, is remarkable for its brilliancy, and its widely extended and varied ramifications, which consist of vast rocky ridges and hollows alternately, with cavities of great extent and depth; the bright circular spots of this place are considered to be insular mountains, or peaks, highly illuminated."

The Moon's Surface - Fracatorius

"This spot is situated on the south-western part of the moon's disc, or on the right side, about one-fourth of her diameter from the lower edge. Its upper portion is a vast hollow; and on its lower, or southern border, are two remarkable cavities of great depth, and bordered by an annular ridge of high rocks, from which radiates an extensive straight ridge of heights, brightly illuminated; smaller mountain peaks are interspersed; and on the right, or western side, a remarkable elevation is seen, having a high annular ridge surrounding it, and an insulated peak in its centre."

The Moon's Surface - Tycho

"This is the remarkable spot, on the lower part of the moon's disc, which is always distinctly visible to the naked eye, and which seems the centre of those radiating lines of spots, which richly cover the south-western, or right-hand lower portion of the moon. Caverns, or hollows, occur most frequently in this quarter; and it is from this circumstance that it is the most brilliant part of the moon's surface. The mountainous ridges, which encircle the cavities, exhibit the greatest quantity of light; and, from their lying in all directions, with an uniform distribution, and yet radiating from the central spot, they seem passage to the vast cavity in which the bright spot is situated. The cavity is estimated to be fifty miles broad, and nearly three miles in depth."

There is very little information online about this book or its author. Originally published in 1840, Charles F Blunt's educational book on astronomy incorporated an 1836 illustrated book, 'Uranographia'^, by an Elizabeth Blunt (relationship to CF Blunt unknown). The 1842 edition of Blunt's 'Beauty of the Heavens' became very popular apparently. [An 1840 copy sold for ~$1000 in 1995]

Blunt included over one hundred illustrations, employing the relatively new printing process of lithography, and the 'greasy crayon' appearance of this technique is quite prevalent. I tend to think it signifies an unpractised or even an unsophisticated print artist; most likely new to the printing format. However it doesn't detract from the overall design accomplishments of the book and the appearance is made all the more attractive with a hand-coloured finish.

I thought it greatly worthwhile to type out a fair sampling of the text, if only for my own amusement. The writing is fabulous: ponderous verbosity one moment, lyrical and poetic the next. I sense a bit of a struggle between the scientist aiming for accuracy and an educational showman hoping to popularise his favourite subject matter. Overall, I think he did a pretty good job for the 1840s; the book has integrity.

All the images above are cropped from their full page layout, with only one image having some peripheral illustration detail removed, as I recall. There is a whole other section of 'painterly'-style illustrations in the book that are not represented at all above.

- 'The Beauty of the Heavens : a Pictorial Display of the Astronomical Phenomena of the Universe', 1842 by Charles F Blunt is hosted online by the magnificent Swiss library e-rara platform for rare books. [note the thumbnails link] [e-rara homepage]

- This post comes via a very good entry from the Digital Collections blog out of Zurich's Swiss Federal Institute of Technology [trans.] [T] [blog homepage | trans.]

- 'The Beauty of Heavens' is available in full on googlebooks (from NYPL) : the illustrations are in colour but it's not as nice a copy as above.

- Previously: astronomy ::: astrology ::: science.