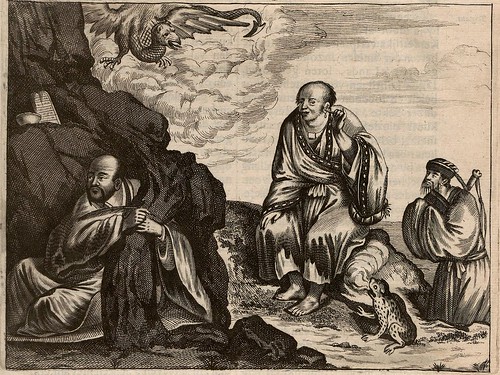

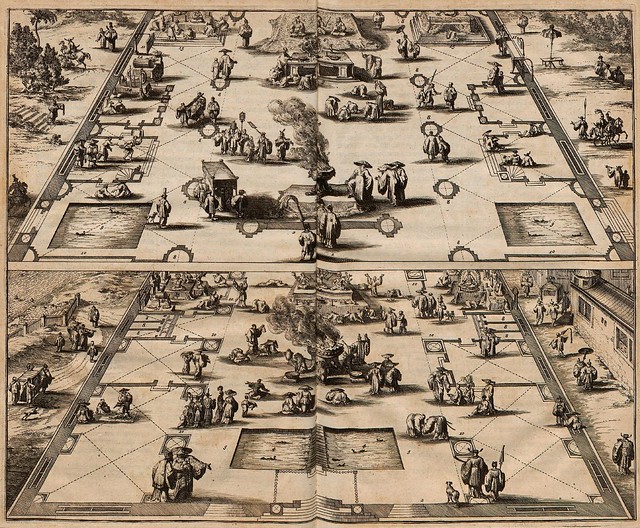

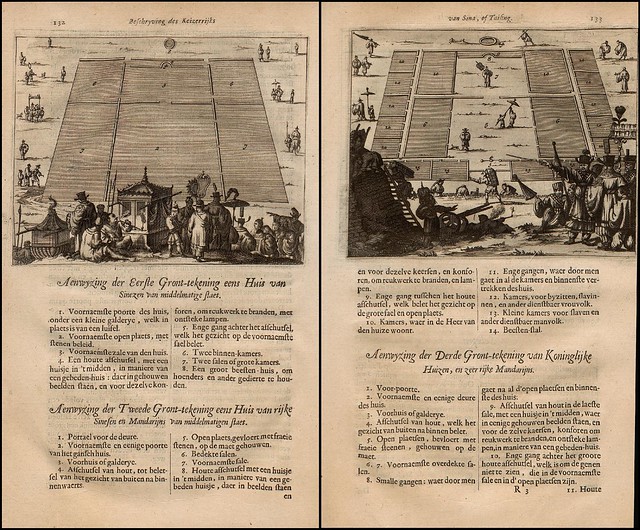

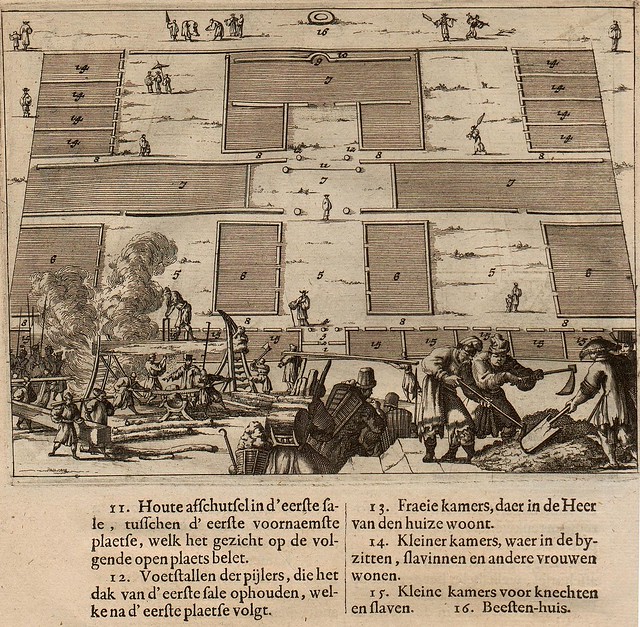

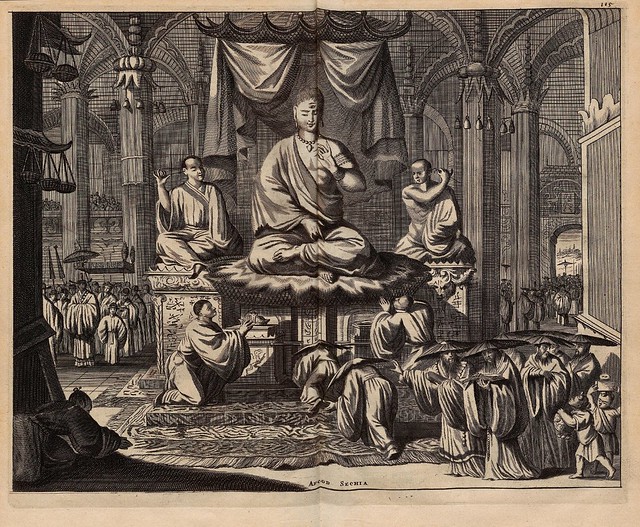

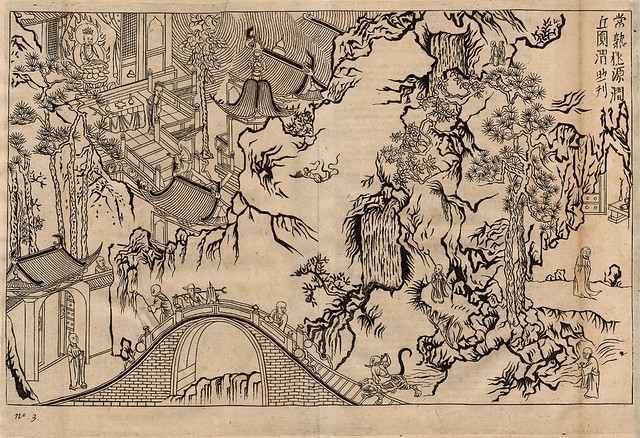

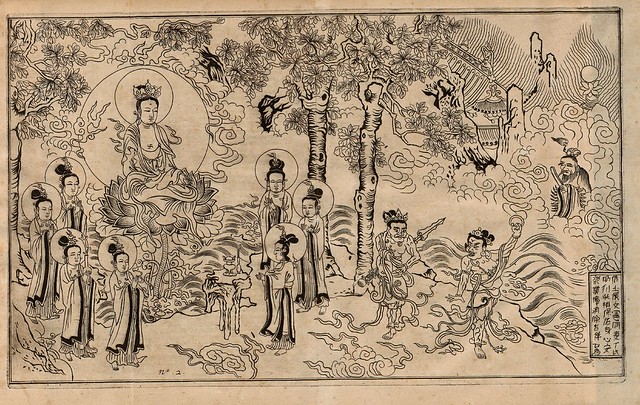

Engravings of religious, civic and natural scenes of China

as understood or believed by Europeans in the 1670s

[All the images have been cropped but I don't recall doing much

in the way of background cleaning or any other adjustments]

Despite never leaving his homeland, Amsterdam clergyman and doctor, Olfert Dapper (1635-1689), became an historical travel writer during the Dutch ascendancy in the Golden Age of exploration and discovery*.

The book featured above was just one title from a renowned body of work Dapper turned out, introducing an enthusiastic public to little known exotic locations from around the world. What Dapper may have lacked in first hand experience, he more than made up for in academic diligence over a quarter of a century of painstaking geographical and ethnological research.

After publishing an initial history of Amsterdam in the early 1660s, Dapper went on to write valuable and well respected books on Africa (his best-known), Persia, Asia, Georgia, Arabia and, of course, China. Far from being mere repetitions of earlier works though (as I admit I was expecting to discover), Dapper's books appear to have been rather exceptional in the world of educational scholarship for their time:

"Dapper avoided all ethnocentric connotations and became the first person to adopt an interdisciplinary approach, weaving together the separate threads of geography, economics, politics, medicine, social life and customs. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Dapper produced a genuine work for posterity, not just a compendium of exotic curiosities." [source]The illustrations for Dapper's 'Description of China' were undoubtedly produced by Jacob Van Meurs, a fellow countryman with his own celebrated reputation as cartographic engraver, who collaborated with Dapper on a number of projects. The visual recording of the country runs the gamut from what is likely faithful renderings of idols and religious and civil buildings from Taiwan and the Mainland, to mystical approximations or downright absurdities and fanciful botanical and biological specimens.

A few of the illustrations are obviously produced by, or copied after, traditional Chinese artists. Dapper relied on a large number of sources, including first hand visitor reports, and it's logical to assume that some of the illustration work was modelled after earlier efforts or became exaggerated the further away from the original source or travel report they got. If you publish a new style of book (travel literature) with outlandish and fabricated pictures that can't be readily checked for accuracy, so much the better for publicity and profits no doubt.

- 'Beschryving Des Keizerryks Van Taising Of Sina: Vertoont in de Benaming, Grens-palen, Steden, Stroomen, Bergen ... Tale, Letteren, &c. ; Verciert met verscheide Koopere Plaeten' is online in full at Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg (1670) [click anything below 'Inhalt' and then on 'Vorschau', up top, for thumbnail pages of the whole book] {the middlish Dutch translates approximately to: 'Description of the Empire of Taising or China: outlined through the place names, border markers, cities, streams/rivers, ... language, letters, etc and illustrated with various copperplate engravings'} .

- The Olfert Dapper Museum in Paris is bilingual and includes about the best biography of our protagonist online [W].

- See the previous Conjuring 17th Century Japan BibliOdyssey post that shows more of Jacob van Meurs' characteristic illustration style. (I was very tempted up above to quote myself quoting myself from my original quote, but I feared the blog would collapse under the weight of rhetorical recursion, despite said quote from said post from unsaid book still having merit)

- Books featuring - Olfert Dapper & Jacob van Meurs.

- The Digital Library of Dutch Literature (DBNL) biographic/bibliographic record for Olfert Dapper [T]

- Thanks Nina!

- Addit: One particular book (series) that conveyed insight into the true nature of Dapper's work - at least, seen in snippets - 'Asia in the Making of Europe' by Donald F Lach (1990s)

No comments:

Post a Comment