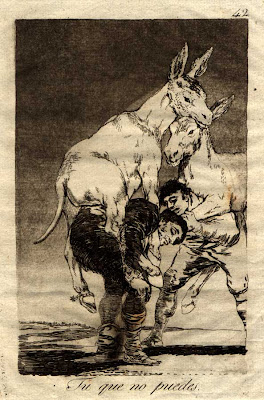

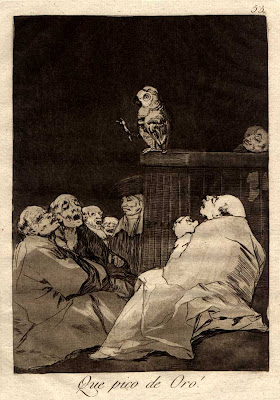

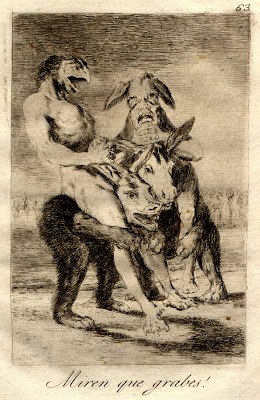

In 1799 Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) published a series of 80 prints called 'Los Caprichos'. In his masterly hands the aquatint etching technique cloaks the line art with subtle and varying tonal effects. This afforded Goya the opportunity, as biographer Robert Hughes says, to

"exalt the scribble, the puddle, the blot, the smear, the suggestive beauty of the unfinished--and, above all, the primal struggle of light and dark, that flux from which all consciousness of shape is born."Like the artist himself, 'Los Caprichos' are complex and open to a range of interpretations. Goya suffered from what seems to have been a disabling bout of meningitis in 1792 which left him stone deaf for the remainder of his life. The illness and resulting alienation and depression provided him with a unique insight into a nightmare world of torment that he so ably transfers to his prints.

Goya lived in a time of social upheaval with the French Revolution, the religious excesses of the Inquisition and the progressive thinking of the Enlightenment manifesting as significant influences. He attacks all manner of human superstition, prejudice, hypocrisy and stupidity in his etchings, whilst subtly mocking the church and state for keeping the people in misery and ignorance.

To avoid alienating his benefactors at Court and to protect himself from the wrath of the Inquisition, Goya masks his satire with the inclusion of demonic and perverse fantasy figures that defy a single understanding. This code of symbolism in the series has provided scholars with a rich vein to mine and has been referred to by some as visual language.

- The images above - the best set online in my opinion - come from the Calcografía Nacional site. It does require some interpretative clicking.

- The easiest place to see all 80 etchings from 'Los Caprichos' is at wikimedia commons (sourced from Arno Schmidt Reference Library).

- Goya at Biblioteca Nacional de España (Las Estampas).

- The Hughes quote above comes from an article by Linda Simon - 'The Sleep of Reason' - at The World & I.

- Francisco de Goya y Lucientes - a host of links.

- Mouseover the images above (which were uploaded at full size) for spanish and english titles - the latter come from the Davison Art Center at Wesleyan University.

No comments:

Post a Comment