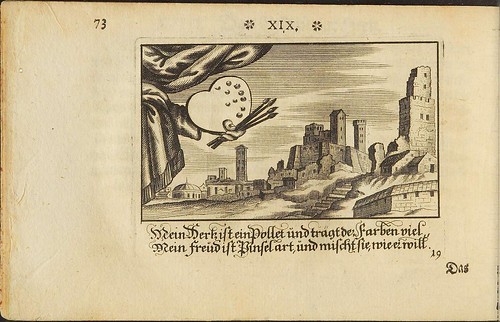

"It cannot be denied that one emblem is easy, another difficult; one good and penetrating, the other bad and simple; one to be interpreted as one thing, another pointing to many different matters. The best are, in my opinion, those in the middle that are neither much too high, nor much too low; that can certainly be understood, but do not immediately lie open to all and sundry." [ Georg Philipp Harsdörffer]

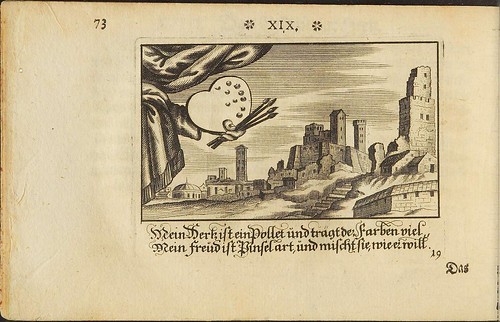

Mein Hertz ist ein Pollet ünd trägt der Farben viel

Mein Freüd ist Pinselart, ünd mischt sie wie er will.

My heart is a pallet and carries colors many

My joy is brush art and mixes them as it will

The colorful Heart (adjacent text)

"The Artists' Commendation"

"When once upon a time on Parnassus the famous artists wished that a memory of their miracle-work might be preserved in the temple of eternity, such petition was answered with merciful compliance: Albrecht Dürer / Michael Angelo / Tician / Sandrad / Merian and many others have adorned the walls with their paintings and most intellectual inventions and artificially* preserved and delightfully decorated the appearance of many decaying things."

*(with a play on Künstler - "artist" - and künstlich - "artificial")

"Zeno, founder of Stoic philosophy, engaged in this and said that the heart of man is the right temple of eternity, which should become the most handsomely adorned with images of the virtues. The heart, said he, is shaped like a painter's pallet; all manner of colors are on it, and art consists of the same masterly use and for the application (? "Werkbringung") of the high colors of virtue and the dark shadows of vice. Apollo hereupon gave this response: That both (these) should be together, a wise man's house should be adorned with beautiful paintings, his heart though with comely virtues."

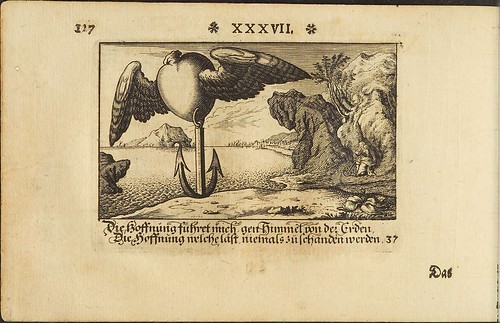

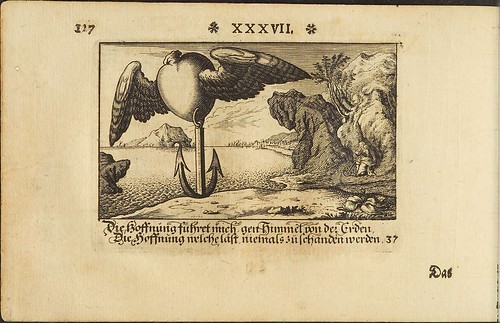

Die Hoffnung führet mich gen Himmel von der Erden,

Die Hoffnung welche läßt niemals zu schanden werden.

Hope leads me from earth toward heaven,

The hope that never lets one come to ruin.

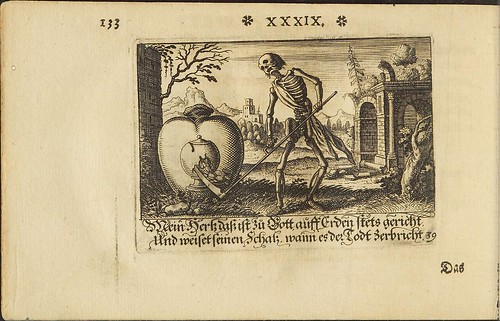

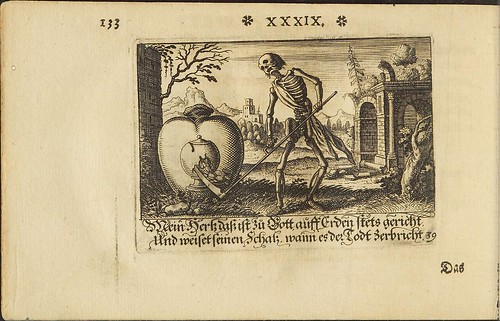

Mein Herz daß ist zu Gott auff Erden stets gericht,

Und weiset seinen Schatz wann es der Todt Zerbricht.

My heart – that is on earth ever aimed at God,

And shows its treasure when Death shatters it.

Mein tief verwundes Herz kan niemals werden heil,

Dar micht der kalte Brand folgt nach den liebes Pfeil.

My deeply wounded heart can never become whole (i.e. heal),

For after the arrow of Love follows the cold fire.

[ding!]

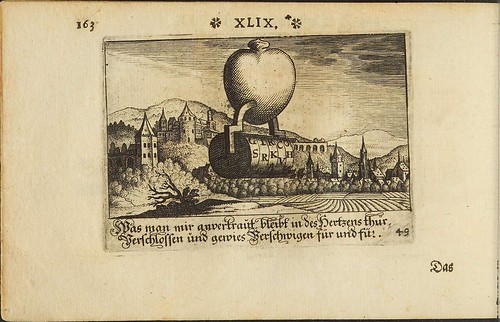

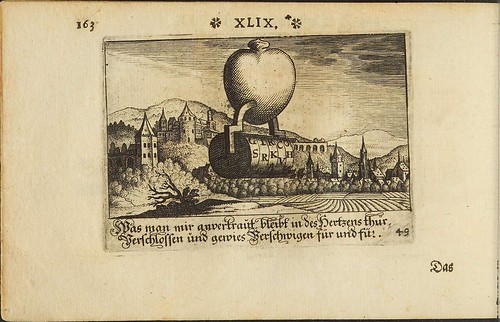

Was man mir anvertraut bleibt in des Herzens thür

Verschlossen und gewies Verschwigen für und für.

What one entrusts to me remains locked in my heart’s

Door and surely kept in silence for ever and ever.

So leicht der leichte Wind umbtreibt daß Kinderspiel,

So leichtlich wendet sich mein Herz von seinem Ziel.

As lightly as the light wind pushes round the children’s toy,

So lightly turns my heart from its goal.

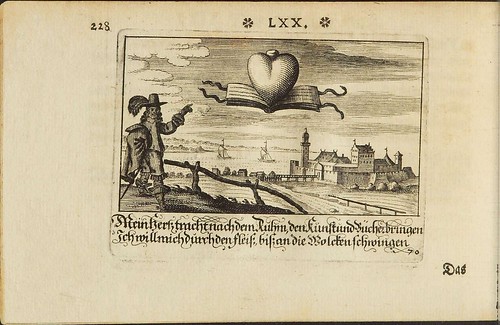

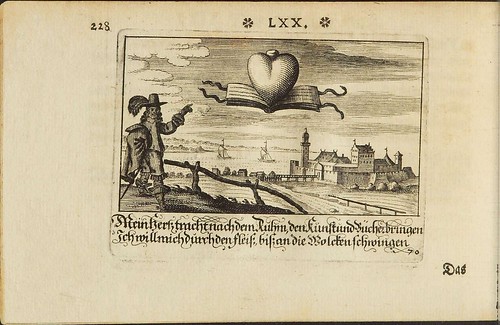

Mein herz tracht nach dem Ruhm den Kunst und Bücher bringen.

Ich will mich durch den fleiß bis an die Wolcken schwingen.

My heart seeks the glory that skill and books bring.

With diligence, I want to vault up to the clouds.

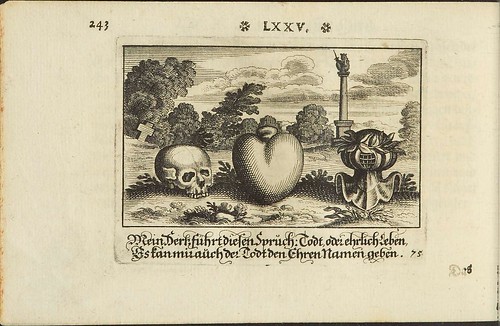

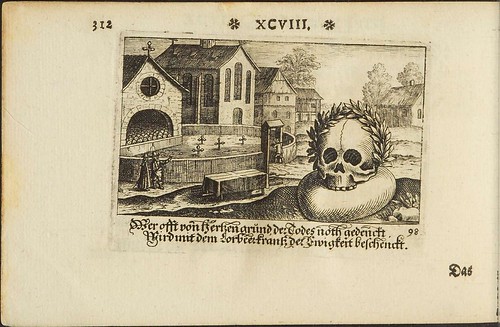

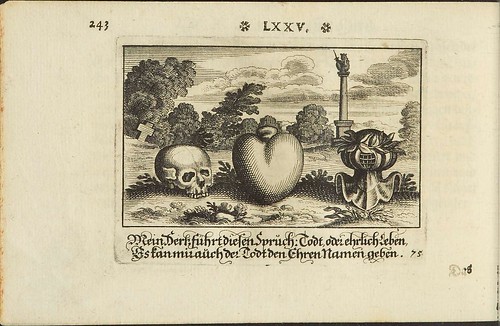

Mein Herz führt diesen Spruch: Todt, oder ehrlich Leben,

Es kan mir auch der Todt den Ehren Namen geben.

My heart keeps this saying: Death, or honest life,

Even Death can give me a noble name.

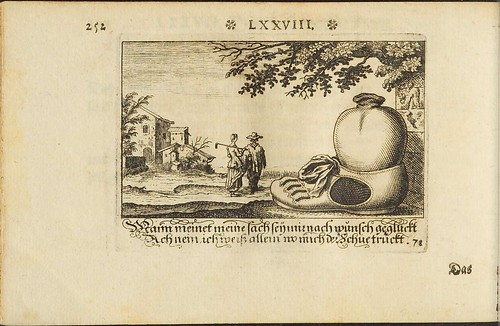

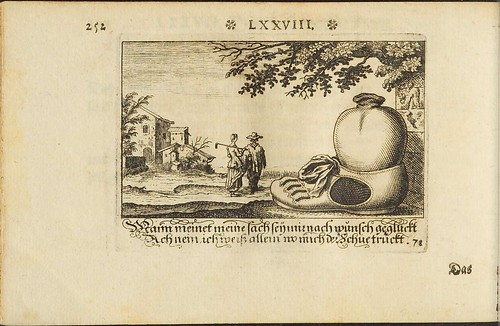

Mann meinet meine sach sei mir nach wunsch geglückt

Ach nein, ich weiß allein wo mich der schue trückt.

People think my business has succeeded as I wished.

Alas no, I alone know where my shoe pinches me.

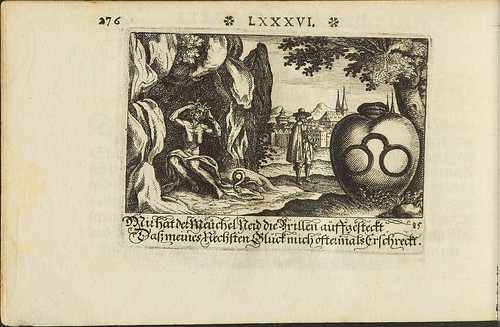

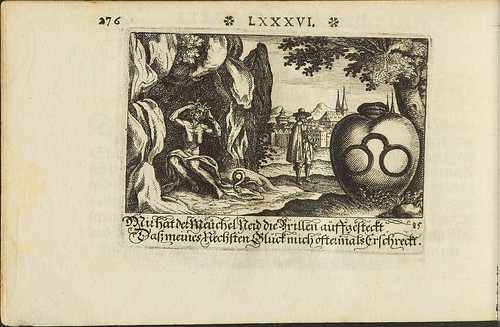

Mir hat der Meuchel Neid die Brillen aufgesteckt,

Daß meines Nechstens Glück mich oftermals Erschreckt.

Treacherous Envy has put glasses on me,

So that my neighbor’s luck often terrifies me.

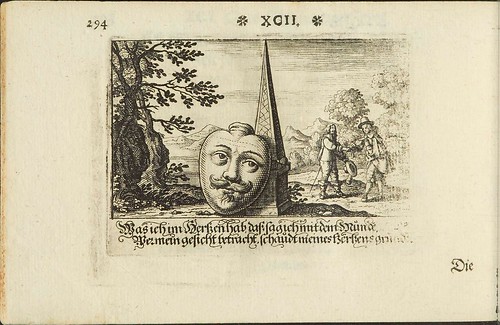

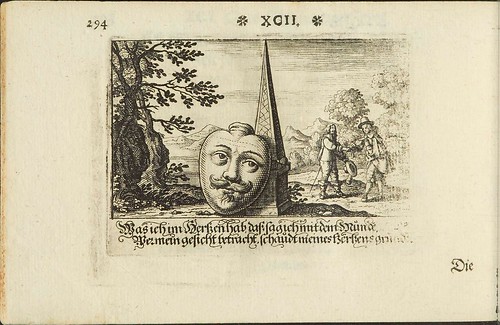

Was ich im Herzen hab, das sag ich mit dem Munde.

Wer mein gesicht betracht, schaudt meines Herzens grunde.

What I have in my heart, that say I with my mouth.

Who looks upon my face, sees the bottom of my heart.

Known generally as

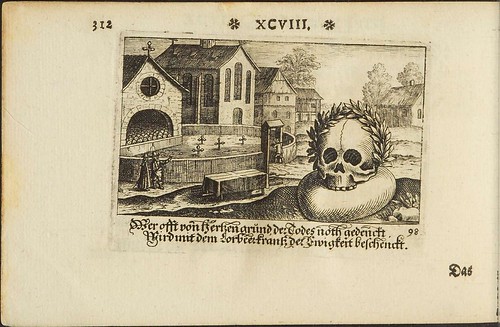

'Das erneurte Stamm- und Stechbüchlein', the long title form of this fairly orthodox emblem book from 1654 translates as:

'The Revised Compendium and Engraving Booklet [with] hundreds of spiritual and secular heart seals/mirrors for a particular illustration of the Virtues and Vices presented and explained with hundreds of poetic conceits by Fabian Athyrus, devout in the praiseworthy Intellectual Arts'

The current academic belief has it that Fabian Athyrus is a pseudonym for the German Baroque poet and emblem fancier, Georg Phillip Harsdörffer. This recent post -

The Odd Baroque - gives some background

(and more odd pictures) about Harsdörffer's interesting role in championing German literature during the 17th century.

The present work is a collection of moral emblems in which the recurring symbolic motif in the

figura is a heart. As the title indicates, the collection seeks to advise the reader about vices and virtues in life and does so in a visual sense by displaying variations of a picture of the heart - which might be taken to be, say, the spiritual wellbeing or goodness of a person, as it still often is today - in a series of contexts that convey an overall allegorical message. The emblems are augmented by a motto and accompanying written elaboration.

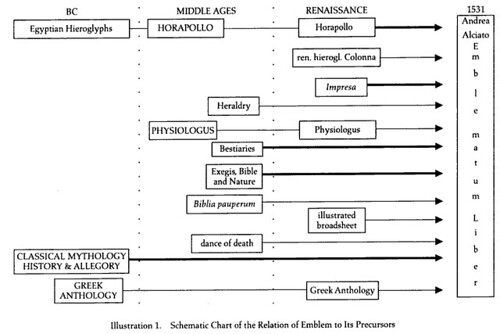

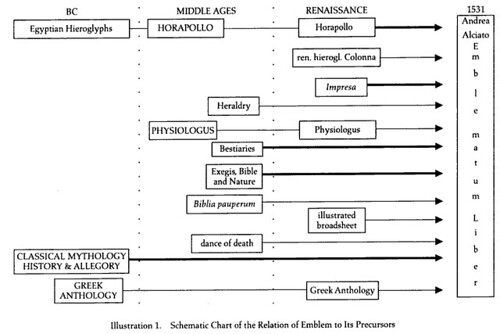

The majority of

emblem books were published in the 16th and 17th centuries with the first being Andrea Alciato's

'Emblematum Liber' in 1531. More than six hundred authors were responsible for the publication of more than six thousand emblem books in Europe, when re-releases and translations are taken into account. They cover a vast amount of subject matter and their complexity and diversity have ensured they provide a deep well for ongoing scholarly research. The chart below (© Peter M Daly) gives some indication of both the antecedents and complicated references associated with Alciato's book, which served as a model for subsequent permutations of the genre.

Biography of Georg Phillip Harsdörffer from Encyclopaedia Britannica:

"German poet and theorist of the Baroque movement who wrote more than 47 volumes of poetry and prose and, with Johann Klaj (Clajus), founded the most famous of the numerous Baroque literary societies, the Pegnesischer Blumenorden (“Pegnitz Order of Flowers”).

Of patrician background, Harsdörfer undertook university studies and an extended Bildungsreise (“educational journey”) through England, France, Italy, and the Netherlands. In 1632 he became a junior judge in Nürnberg and in 1655 a member of the town senate. His poetry, typical of the Baroque movement, is characterized by elaborate and sometimes playful rhetoric and exaggerated poetic forms. He laid particular emphasis, in his poetry and in his theoretical work, on Klangmalerei (“painting in sound”).

His most famous theoretical work, a handbook for Baroque poets, is ironically titled 'Poetischer Trichter, die Teutsche Dicht- und Reimkunst, ohne Behuf der lateinischen Sprache, in VI Stunden einzugiessen' (1647–53; “A Poetic Funnel for Infusing the Art of German Poetry and Rhyme in Six Hours, Without Benefit of the Latin Language”). Widely read in its time was 'Frauenzimmer Gesprech-Spiele' (1641–49; “Women’s Conversation Plays”), which, like many of his works, had a didactic purpose. It consists of eight dialogues aimed at teaching women all they need to know to become useful members of society. His 'Pegnesisches Schäfergedicht' (1644; “Pegnitz Idyll”), written with Klaj and modeled on the English poet Sir Philip Sidney’s Arcadia, did much to spread the fashion of pastoral drama. Harsdörfer also translated works from French, Spanish, and Italian."