'The Greenwich Pensioner'

by N. Carpenter; Charles Dibdin, late 18th cent.

"This robust, popular image illustrates the text of Charles Dibdin's well known song, 'The Greenwich Pensioner' which is printed below it (not shown on photo). The Pensioner, with a left wooden peg-leg, a stout stick under his left arm and a clay pipe in his left hand stands on the north side of the Thames, gesturing towards Greenwich Hospital, the Queen's House and the Royal Observatory in the background with his right hand.

The stern of a small Royal Naval warship flying the red ensign is on the left, with a sprit-rigged river craft, and the Union flag flies above the Governor's House in the King Charles Court on the right. The Pensioner's position is falsely elevated, producing an aerial perspective of the Grand Square behind, with Rysbrack's statue of George II in the centre. The background design may derive from Rigaud's much earlier print of the Hospital, or similar ones which adopt this perspective."

More on the Greenwich Pensioner/Royal Hospital for Seamen, Greenwich:

I,

II.

'Emma Hart afterwards Lady Hamilton as the goddess

of health while being exhibited in that character by

Dr Graham in Pall Mall' by Richard Cosway

c. 1785.

"A pen and wash sketch showing Emma Hart enacting a ‘tableaux vivant’. She wears loosely flowing classical robes and Greek-style sandals and holds a ritualistic goblet. She is posing as Vestina, the goddess of health, an attitude she adopted while employed with the well-known quack doctor, Dr James Graham.

He opened a Temple of Health and Hymen, initially in the Adelphi and later at Schomberg House, Pall Mall. Magnificently fitted out, it attracted crowds who visited to hear Graham’s lectures on the advantages of electricity and magnetism. He also advocated healthy living and personal beauty, leading to happiness in body and mind, while the Temple was further famed for its ‘celestial bed’ in which infertile couples could pay a large sum to spend the night as an aid to conception – or so ran the promotion.

Graham also endorsed the frequent use of mud-baths and was reputedly seen immersed in mud while wearing an elaborately dressed wig, accompanied by Emma, with her hair elaborately dressed with powder, flowers, feathers, and ropes of pearls.

Emma’s ‘attitudes’, in which she portrayed contrasting emotions through gesture, expression and a variety of props were more fully developed after she became Sir William Hamilton’s mistress at Naples in 1786, and later his second wife. Hamilton encouraged this, tutoring her in antique gesture based on his knowledge of classical sculpture and vase decoration, supervising her performances, and having artists record them – Frederick Rehberg’s drawings being published at his expense.

The overall result was that she was celebrated throughout Europe for this unique form of personal performance. This drawing is an early record of her in such a role and one that also captures her erotic youthful beauty."

"..In her performances of these ['attitudes'], which she first began about 1786, Emma adopted poses taken from classical sculpture or Renaissance painting: at one point Sir William Hamilton even constructed a special box with a black border for her to pose in, to imitate more closely the appearance of a framed painting.

Numerous contemporary descriptions praise both her skill at adopting poses that would have been easily recognizable to connoisseurs steeped in a classical education and her own naturally ‘classical’ beauty. Rehberg’s publication was highly popular, running to several editions: so much so that it was lampooned in 1807 by (probably) James Gillray, who substituted for the graceful, classically proportioned body of Rehberg’s prints a ‘considerably enlarged’ figure, truer to the by then excessively fat Lady Hamilton, in what was termed a ‘new edition ... humbly dedicated to all admirers of the grand and sublime’. "(eg.)

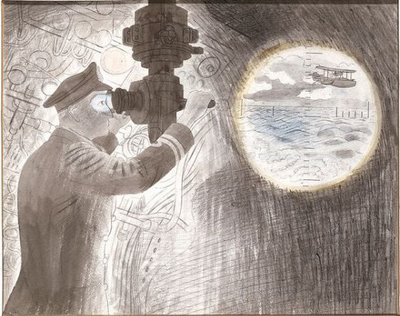

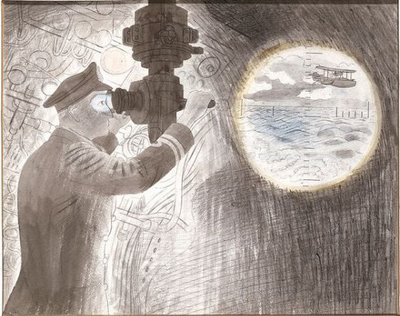

'Submarine Series. Officer viewing

through periscope' by Eric Ravilious 1940.

"In 1940 Ravilious became one of the first official war artists. During the summer he was at HMS 'Dolphin' at Gosport drawing the interiors of submarines, sometimes at sea. He had already conceived the idea of a set of submarine lithographs intended as a children's painting book, and in November he set to work."

[He died in 1942. See:

Imperial War Museum exhibition; all the illustrations from

'High Street';

gallery of illustrations and crockery;

homesite.]

'The Ton at Greenwich. A la Festoon dans

le Park a Greenwich' by Darly 1777.

"A satire on the size of French-inspired bouffant hairstyles and their protection, with the Observatory on the hill on the right. The print is also an early image of an umbrella - carried by the servant. This was invented (or at least popularized) by Jonas Hanway, founder of the Marine Society, which educated and fitted out orphan boys for a career at sea."

'Le San Culote' [Sans-Culotte], figurehead Revolutionary

French ship circa 1795 {from the French School}

"It was usual for ships to bear figureheads with political or ideological meanings. This is one of two drawings of the French Revolutionary ship ‘Sans-Culotte’, the other of which shows the stern. Here the starboard profile view of the prow focuses on the figurehead, the icon of the Revolutionary ideal, the Jacobin ‘sans-culotte’.

He is, however, a fusion of various Revolutionary iconographies. The Republic took as its political model the ‘polis’ of the classical Greek republic, and openly adopted severely rational, neo-classical cultural ideals in emulation of the classical past. The mythological hero Hercules was also adopted, along with the female icon Marianne, as the incarnation of French Revolutionary principles.

Here, therefore, the ‘sans-culotte’s’ dress is transformed into a classicized toga, and, while clutching the ‘fasces’ (the bound rods and axe that represented Roman justice) with his left hand, he holds in his right a Herculean club. On the other hand, his contemporary identity is also represented, somewhat incongruously, by his wearing typical French 18th-century footwear and the obligatory ‘bonnet rouge’."

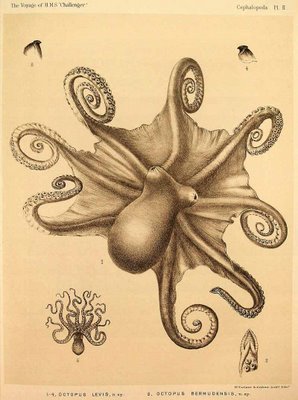

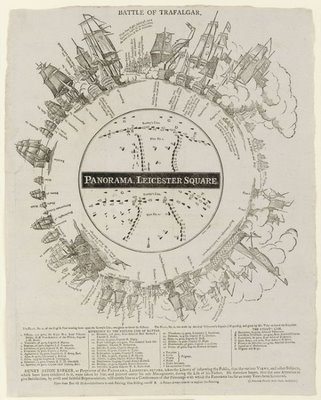

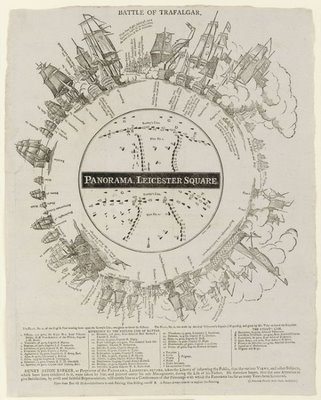

'Battle of Trafalgar. Panorama, Leicester Square'.

Lithography by J Adlard after Henry Aston Barker

c.1806.

"Cleverly painted, masked and lit by daylight from above, these circular panoramas gave the illusion to those standing on the central viewing platform that they were really in the landscape, seascape or battle scene that were the usual subjects. The panorama was invented about 1787 by Robert Barker of Edinburgh. From 1794 to 1863, he and his successors exhibited many such spectacles in ‘The Panorama’, his purpose-built premises in Cranbourne Street, Leicester Square, where the largest views – including this one of Trafalgar, shown in 1806 – were about 30 feet high by 90 feet across (9 x 27m), on 10,000 square feet (930 sq. m) of canvas.

Many other showmen copied Barker and circular panoramas became common across Europe and America. A few survive (as well as modern ones) but the last large circular panorama of Trafalgar was painted by Philip Fleischer in 1890. It was seen in Edinburgh and Manchester before being shown at the 1891 Royal Naval Exhibition at Chelsea, and then toured on the Continent.

When they met at Palermo in 1799, Nelson thanked Barker for prolonging the fame of the Battle of the Nile in a Leicester Square panorama. This is the printed viewer’s ‘key’ to the version of Trafalgar painted in the year of Barker’s death by his son Henry. It was displayed for over a year from about 14 May 1806 to 25 May 1807."

Unfortunately, I couldn't track down any images of Fleischer's painting - '

image unavailable' (near the end of the page). At least it put some ideas and sites into my orbit for a future post.

'Dresses a la Nile respectfully dedicated to the

Fashion Mongers of the day' by W. Holland 1798.

"A gentle lampoon against British fashionable society, making facetious suggestions for ways to incorporate the topical news of Nelson’s victory over the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile on 1 August into the latest fashions.

It was commonplace for people to display patriotic sentiment or political opinions (for example, for the campaign for the abolition of the slave trade) through dress or other accoutrements, but this satire takes this trend to ridiculous extremes, with its overabundant and absurd Egyptian references. It also maintains a staple iconography of satirical prints, treating the excesses of fashion.

On the left, the woman is virtually mummified in her white dress decorated with crocodiles. Opposite her, the man’s costume is even more extravagant, consisting of crocodile skin coat, waistcoat and reptilian boots. His hat also sports a bright yellow crocodile. They stare at each other in mutual astonishment at the other’s appearance. To complete the topical references, and by way of explanation of the outfits, both wear hats with the motto ‘Nelson and Victory’."

'Bray Album: A Sailor bringing up his hammock,

Pallas, Jany 75' by Gabriel Bray 1775.

"In 1991 the Museum acquired a group of drawings by Gabriel Bray (1750-1823), the second lieutenant on HMS 'Pallas' during a voyage to the coast of West Africa and the West Indies, 1774-75, under Captain the Hon. William Cornwallis. The drawings are remarkable because they show aspects of everyday life on board a Royal Navy ship during the 1770s, the decade of Captain Cook's three voyages.

The drawings are rare if not unique in showing sailors and marines about their daily duties - in this a example a sailor carrying his hammock. This drawing, or one like it, is also shown being inspected in Bray's sketchbook by James Cornwallis - a relative of the captain's who was also on the voyage - in a portrait drawing of him from the same group."

'A Correct Plan and Elevation of the Famous French Raft

constructed on purpose for the Invasion of England and

intended to carry 30000 men, Ammunition stores &c &c.

Engraved from a Drawing made by an Officer at Brest and

now in Possession of the Publisher' {British School, 18th cent.}

"Early in 1798 there were reports of a planned French invasion of the southern English coast, with the build-up of troops in the northern French ports. On the French side there was a belief that their invading army would be broadly welcomed by the majority of ordinary British people.

By contrast, across the Channel fears of an invasion induced the promulgation of a fable about an enormous raft that the French were supposedly constructing in order to transport huge numbers of French soldiers to England. Several prints, of which this is an example, were produced claiming to be based on eyewitness accounts or other authentic information. They vary in the raft’s reported carrying capacity, most claiming that 60,000 troops could be transported.

This print, which shows the raft as the impossible product of severe rational geometry, combined with the fantasies of Baron Münchhausen and Noah’s Ark, claims just 30,000 capacity. It is difficult to know how seriously prints such as this were intended to be taken. While there was genuinely founded fear of invasion, there was also widespread ridicule of the idea of a raft, including a theatrical afterpiece on the subject. J. C. Cross’s ‘The Raft, or both Sides of the Water’ had its first performance at Covent Garden on 31 March 1798, with the predictable denouement of the raft being blown up."

'A new Machine (or Raft) to cover (or protect)

the Landing of the French on their intended

Invasion of England etc' by William Winton 1798.

"This is another variation on the supposed raft being built by the French for the invasion of Britain in early 1798. Unlike other prints produced during this wave of paranoia in London, which represent the vessel as an excessively fantastic contraption more appropriate to the tales of Baron Münchhausen, this print pares it down to a severe geometric symmetry to assert its claim to being based in fact. Indeed, a greater air of authority is lent by the claim that the engraving is made after an original drawing by a French prisoner of war, and by the wealth of statistical detail in the caption. The machine is described as:

‘Flat; 2,100 Feet long, and 1,500 Feet broad; has 500 Cannon round it, 36 and 48 Pounders; at each end is two Wind Mills, which turns Wheels in the Water at every point of the Wind to Navigate; in the middle is a Fort enclosing Mortars, Perriers, &c. It carries 60,000 Men, Cavalry, Infantry, and Artillery.’

Nonetheless, this does not disguise the unseaworthiness of the ‘new machine’, and neither is there any firm evidence that such a vessel was being constructed on the north French coast at this time."

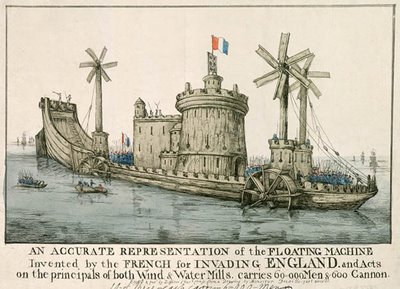

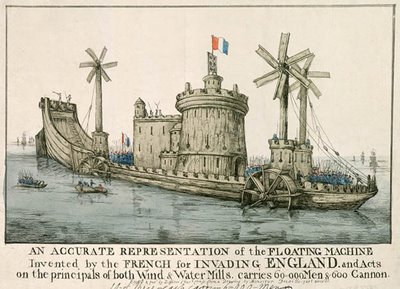

'An Accurate Representation of the Floating Machine Invented

by the French for Invading England and acts on the principals

of both Wind and Water Mills etc' by Freville; Deighton

c.1805.

"Another print responding to the invasion scare of early 1798 and the rumours of an enormous raft that the French were supposedly constructing on the Channel coast in order to land vast numbers of troops. Here it is claimed that the vessel could carry 60,000 troops, though it is difficult to see how it could be believed that such a bizarre, Heath Robinson contraption as this could ever put to sea. Combining wind and watermills, with an enormous ‘Gothic’, Bastille-like tower and castle in the centre, it seems to recall contemporary fantasies about the appearance of the Ark."

The UK National Maritime Museum has about 1000 images available from their 'Prints, Drawings and Watercolours' collection.

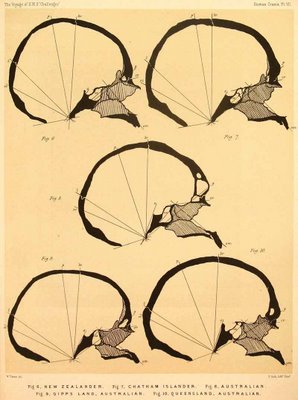

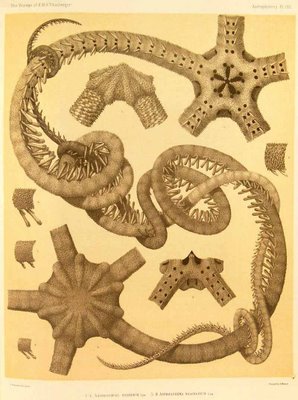

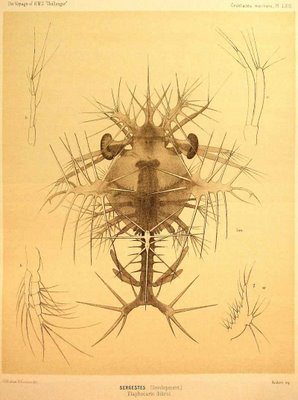

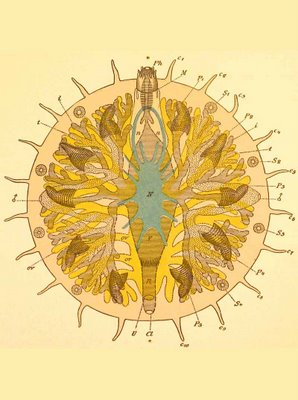

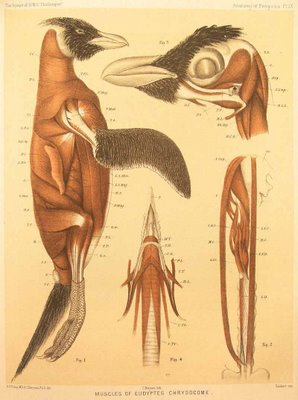

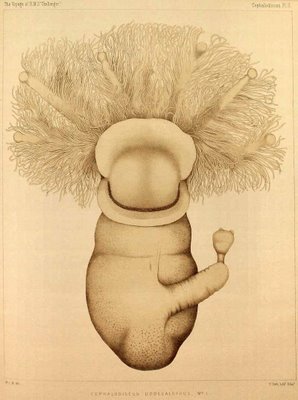

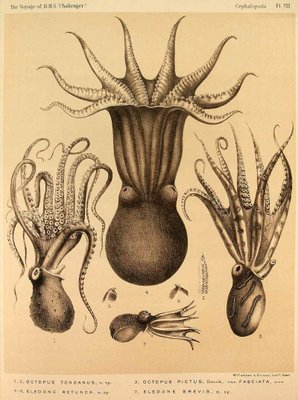

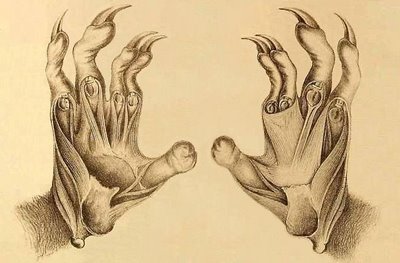

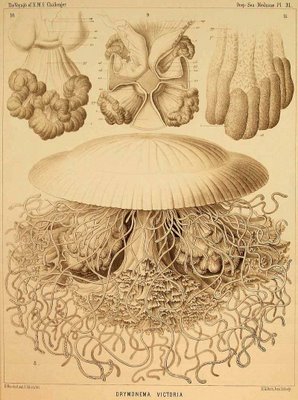

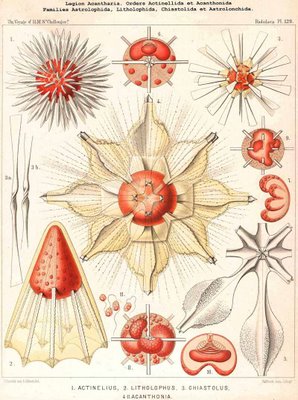

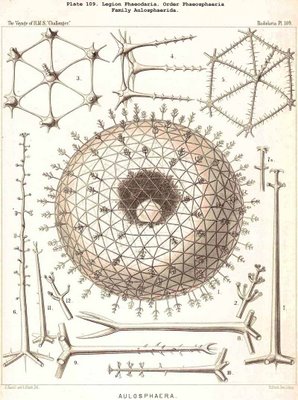

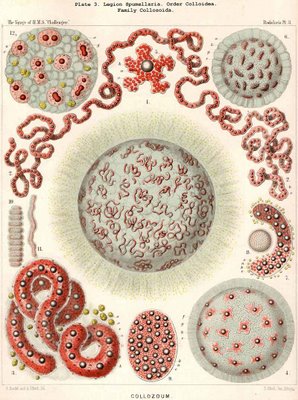

This is an inverted, spliced and 'scrubbed' detail from a plate entitled

This is an inverted, spliced and 'scrubbed' detail from a plate entitled

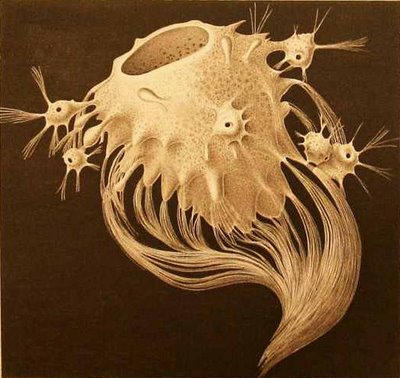

The above 4 images come from the renowned Ernst Haeckel

The above 4 images come from the renowned Ernst Haeckel